Wikipedia

I’ve yet to read Nick Carr’s latest, The Shallows, which takes a pessimistic view of the effects of writing and scanning tweets, SMSs, IMs, etc. on our neural wiring.

It’s on my reading list. Certainly his claim that our attention spans are being stunted, which may ultimately degrade our overall ability to follow more complex, non-shallow arguments when needed, has made its way into our public arguments on the Internet and always-on digital technology

In his Rough Type blog, Carr recently responded to an essay by Justin Smith that takes an opposite view. Smith, writing for Berfrois, points out that transient, non-deep relationships have been with us since the first “have a good day!” was uttered.

The Internet just turns what were trivial, meaningless interactions within our own small social groups into trivial virtual interactions with our friends, along with a much larger network of “friends”.Continue reading

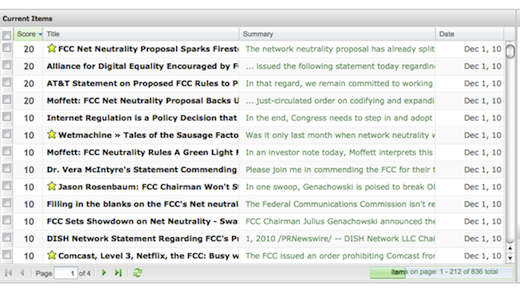

I was finally able to spend quality time with the Parse.ly Reader, an app designed to show some of the capabilities of the underlying Parse.ly platform, called P3, which is currently in beta. To be clear, unlike many other players in the recommendation patch (GetGlue, Xydo, Hunch, etc.), this NYC-based startup is not in the business of providing a direct service to users.

I was finally able to spend quality time with the Parse.ly Reader, an app designed to show some of the capabilities of the underlying Parse.ly platform, called P3, which is currently in beta. To be clear, unlike many other players in the recommendation patch (GetGlue, Xydo, Hunch, etc.), this NYC-based startup is not in the business of providing a direct service to users. Here I’ve been getting excited about new user interface niceties such as voice rec in Windows Phone 7 and Android, while completely missing the bigger picture. The National Science Foundation has announced it will be funding a NeuroPhone, “the first Brain-Mobile Interface (BMI).” This “high risk, exploratory research,” to be conducted at Dartmouth College, involves developing a consumer-level wireless EEG (electroencephalography) headset to interface with a mobile device. From what I can decipher from the proposal abstract, they will study ways to digitize and interpret brain wave activity.

Here I’ve been getting excited about new user interface niceties such as voice rec in Windows Phone 7 and Android, while completely missing the bigger picture. The National Science Foundation has announced it will be funding a NeuroPhone, “the first Brain-Mobile Interface (BMI).” This “high risk, exploratory research,” to be conducted at Dartmouth College, involves developing a consumer-level wireless EEG (electroencephalography) headset to interface with a mobile device. From what I can decipher from the proposal abstract, they will study ways to digitize and interpret brain wave activity.