If you’ve not ever heard of political scientist Robert Axelrod and his computer modeling of altruism in the early 1980s, immediately go and listen to the podcast of a RadioLab show—public radio’s best hour— entitled “Good.”

Do that now.

Skip to around the 41 minute mark, and you’ll hear the start of Jad and Robert chatting with Axelrod. Aside: Often when I read something interesting, I imagine it spoken in a Robert Krulwich voice to decide if it would make a worthy post.

Anyway, “Good” is the best popular introduction I’ve come across as to why we’ve evolved to be civil to others.

The show’s exploration of reciprocal altruism, the big concept underlying the discussion, also explains why we’re inclined to proffer advice on restaurants, camcorders, recipes, child raising, kitchen repairs, etc. in our virtual communities.

Axelrod’s computer modeling experiments took the form of a software contest—kind of an early hackathon—in which programs engaged in repeated trials of the classic prisoner’s dilemma game, wherein there’s a large gain if either party rats out or defects, but smaller benefit when both cooperate by remaining silent.

The gang at Radiolab masterfully explain the various strategies that were coded, and why the two or three lines of the Tit-for-Tat app eventually won Axelrod’s computer tournament.

To summarize Tit-for-Tat: if you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours; but if you hadn’t helped me in our previous interaction, I won’t help you in the next encounter. It’s a combination of “do unto others….” and “an eye-for-an-eye”.

How does this relate to social networking sites? Researchers have observed there’s certain amount of altruistic social capital inherent in our species: in a one-shot prisoner’s dilemma game, in which both parties are told they will never interact again, more that half the subjects were willing to cooperate and accept a smaller short-term payout.

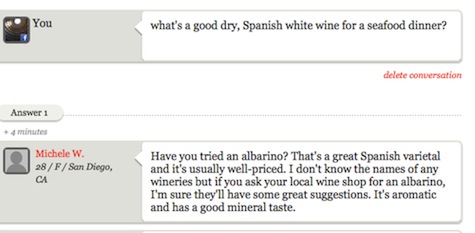

So when I posted my first Aardvark question a few months ago, never having interacted with other ‘Varks, I was delighted to get an immediate answer about a Spanish white wine. Thank you social capital!

Aardvark is a Q&A site with high social-capital.

The long-term issue in these social networks is whether the core group of altruists will be crowded out by more selfish agents—spammers, free loaders—who defect from the social capital contract by not contributing.

Axelrod has an answer. He discovered that the best “nice” strategy in terms of its ability to ward off invaders is Tit-for-Tat, not turn-the-cheek 100% altruism, which can be defeated by a purely selfish strategy.

Which is why in many of these sites, say Aardvark, you’ll get information about a person’s reciprocity, as in how may questions they’ve answered. And then there’s usually game rewards to boost the reputations of the nice, reciprocating members.

In tbe paper referenced below, one game theorist explains how a stable mixture in the prisoner’s dilemma game can have lots of reciprocal altruists with some pure altruists, but not enough for selfish players to exploit and gain advantage over the rest of this nice community.

Not a bad game plan for growing a social website.

Related articles

- Foragers and Foodspotters (technoverseblog.com)

- Rise and Decline of Social Capital (hha.dk)